From Interceptor to Aero Legend – 16 Facts About the Hawker Typhoon

The Hawker Typhoon was a great Second World War aircraft, but it never lived up to its designs intentions. It was intended to be a medium to high altitude interceptor, but the Typhoon would never see this role during its service with the RAF. Instead, it would slide into a few niche roles, roles this airframe particularly excelled at.

Originally an Interceptor

The Hawker Typhoon’s original purpose was to be an interceptor. However while it was very fast for the time, it had a poor rate of climb and handling at heights of over 20,000 ft, which rendered it fairly useless as a high altitude interceptor. These characteristics meant it was employed instead as a low level interceptor, defending Britain from lower level German fighters and bombers.

Designed Around the Engine

The requirements listed by the British Air Ministry stated that they wanted a new fighter that was capable of 400 mph at 15,000 ft, and used a British supercharged engine. Sydney Camm selected the Napier Sabre for the Hawker Typhoon, a 36.6 L 24 cylinder monster arranged in a ‘H’ layout, which produced over 2,000 hp. This was one of the most powerful aircraft engines in the world at the time, but wasn’t the most reliable.

Troubled Development

Like many new machines, the Typhoon experienced its fair share of teething problems early in its development, some of which would never be fully resolved throughout the airframe’s service life. Reliability issues of the Napier Sabre engine led to the delay of the prototype’s first test flight, pushed back to February 1940. The aircraft managed to reach squadrons by late 1941

A New Speed Record

The Typhoon was the first RAF fighter to reach a speed of 400 miles per hour, thanks to its Napier Sabre engine. The Sabre engine was tremendously powerful with RAF Flight Lieutenant Ken Trott saying:

“Rather a large aircraft shall we say, for a single-engine fighter. Terrific power. Quite something to control.”

The Sabre was massively powerful, but ran very rough compared to more classically smooth engines like the Rolls-Royce Merlin V12. It produced a lot of noise, which pilots struggled with during flights.

Effective Weaponry

The Hawker Typhoon was originally designed to carry 12 .303 Browning machine guns, but would eventually be fitted with four 20 mm cannons instead, 2 in each wing. Cannons were increasingly replacing machine-guns as the weapons of choice for fighter aircraft.

Technological advances such as self-sealing fuel tanks and armor plating meant aircraft were getting tougher, too tough for smaller machine guns which could only damage what the projectile hits. The explosive ammunition of cannons countered these advances by detonating within the aircraft, destroying components without having to contact them directly.

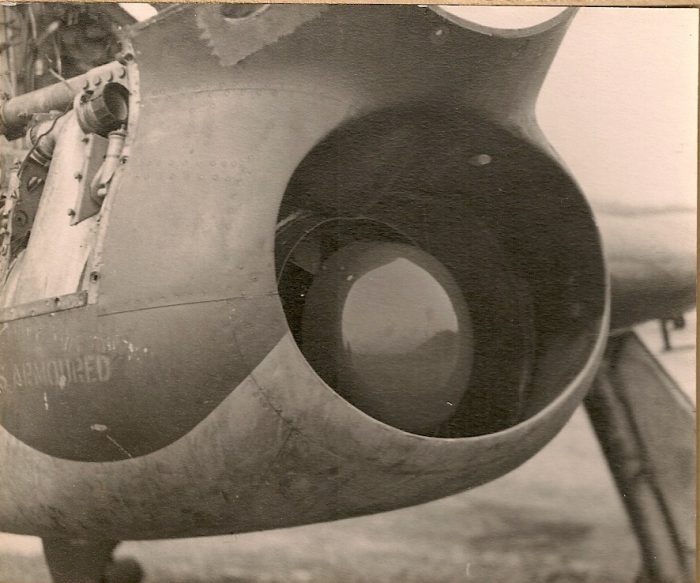

The ‘Chin’

The most distinctive feature of the Hawker Typhoon was the ‘chin’ radiator. This was added early in the aircraft’s development to help cool the massive Napier engine. It was kept throughout the life of the Typhoon. When the Hawker Typhoon had to perform a belly landing, the chin radiator could prove to be lethal, digging into the ground and causing the aircraft to flip over.

The Typhoon update/replacement was the Hawker Tempest, a late war aircraft that solved the failings of the Typhoon. It eliminated the chin radiator, dramatically improving the aircrafts speed, immediately becoming the fastest aircraft Hawker ever built by that time when it reached 466 mph.

Tail Trouble

The Typhoon airframe suffered from a structural tail weakness from the very beginning. It actually killed one of Hawker’s test pilots, Ken Seth-Smith, when his Typhoon broke up in mid-air during speed tests of the aircraft.

The weakness was in the the rear elevator’s mass balance which could tear off at high speed, causing the elevator to violently flutter until it tears off. This was partially fixed with strengthening and bracing around the weak areas, but the fault would never be truly solved on the aircraft.

Almost Withdrawn from Service

After the many issues with the aircraft, some of which have been listed, the RAF almost gave up on the Typhoon, nearly withdrawing the entire fleet from service. Fortunately, Hawker engineers were able to fix most of the problems, creating a serviceable aircraft which proved to be devastating. The main problem remaining was engine reliability.

Finding a Niche

During this time of turmoil for the Typhoon, it did begin to find its feet, particularly against the new German Focke-Wulf Fw 190 fighter.

The Fw 190 is regarded as the best German fighter of the war, remaining to be a terrifying foe all the way up to the wars end. It ended the aerial superiority of the Supermarine Spitfire V, forcing the British to upgrade the Spitfire to counter it. Even the earliest versions of the Fw 190 could reach 400 mph, a speed no British fighter could reach… accept the Hawker Typhoon.

Fw190s equipped as fighter-bombers began making raids against targets on the south coast of Britain, using their superior speed to make a safe getaway. The Typhoon was the only British fighter that could catch up with and destroy these raiders, thanks to its top speed of 412mph. The RAF deployed Typhoons along the south coast of the UK in late 1942 to defend against these attacks, and within days they had destroyed four Fw190s.

This role finally made good use of the Typhoon’s combination of high speed and good low altitude handling. But it was in another role that the Typhoon really made its mark.

Mistaken For the Fw 190

An issue encountered early in the Hawker Typhoon’s service life was that from certain angles and distances it resembled the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, causing many friendly fire incidents. To prevent this, the Typhoon’s undersides were painted with black and white stripes to signify to Allies it was a friendly aircraft. These stripes were precursors to the famous D-Day stripes.

Turning into a Fighter-Bomber

As the RAF and its pilots began better understanding the Typhoon, they realised the airframe was perfect for the ground attack role. The oddly thick wings and powerful engine meant the Typhoon could carry 900 kgs (2000 lbs) of bombs. By mid 1943, every Typhoon coming off production lines were fighter bomber variants.

Under wing racks were added, as well as more suitable tyres to handle the extra weight of the bomb-laden Typhoon on the ground.

Fighter bombers’ close proximity to the ground mean they are often subjected to a hail of small arms fire. Aircraft with air cooled radial engines are much better suited for this, as a penetrating shot into the engine wont cause it to loose coolant and effectively destroy it.

Because of this, 350 kg (780 lbs) of armour plating was added to the sides and bottom of the cockpit and engine compartments, adding protection to the pilot and the delicate 24 cylinder screaming away at the front.

Again because of the extra weight, larger disk brakes were added to help the slow heavy aircraft down on landing. It was found after all the modifications, the aircraft’s top speed wasn’t badly hampered, and its handling was barely affected at all. This is a testament to the strength of the airframe and power of the Napier Sabre.

In this role it was truly devastating, and acted as a terrifying deterrent to enemies on the ground, who would often abandoned their tanks at the mere sight of approaching Typhoons. The stability of the Typhoon at low altitude helped pilots accurately place cannon-fire and ordnance on the target.

Returning the Raids

From 1943, the tables were turned. Instead of intercepting German fighter-bomber raids along the British coast, the Typhoons were now sent on raids of their own against German ground targets in occupied France and the Low Countries.

Adding Rockets

Late in 1943, Typhoons were equipped with rockets for the first time, four under each wing for a total of 8. The rocket used, the RP-3, could be fired singly (later omitted), in pairs, or as a full salvo, controlled by a switch in the cockpit.

Once again, the affect on the Typhoons performance was negligible, leading to a few aircraft receiving an extra rack of rockets below the first, for a total of 12 rockets.

16 could technically be carried, but issues with the racking made this impractical and it wasn’t used in combat.

The targeted destructive power of the rockets turned the Typhoons into a devastating strike force, able to deliver sudden attacks capable of blowing the turrets of German heavy tanks before making a quick getaway.

Supporting D-Day

During the D-Day operations of June 1944, Typhoons were used in tactical raids against German infrastructure. In particular, they targeted communications sites in a relentless series of attacks by both day and night.

Troops engaged in combat on the ground carried radios and smoke grenades, and would call in Typhoons for assistance when needed. The Allied aerial superiority during the D-Day landings allowed Typhoons and other fighter bombers free reign over the skies, attacking German ground targets at will.

Struggling With Normandy

Soon after the Normandy invasion temporary landing strips were cleared for Typhoons to provide continuous close air support to the rapidly advancing allied troops. Within a few days the aircraft started to experienced problems as the engines sucked in coarse Normandy dust, causing wear in the already delicate cylinders, and grounding the aircraft.

This problem needed to be solved fast, so the Air Ministry contacted D Napier & Sons Flight Development Establishment at Luton. Napier immediately reacted by designing, building and test flying a new air filter that was 96% as efficient in just ten hours.

26 Squadrons

By the end of the war, Typhoons made up 26 squadrons of the 2nd Tactical Air Force, which primarily focused on close air support. The Typhoon became one of the deadliest and most affective fighter bombers of the war.

Another Article From Us: Fw 190 – the Bird that Scared the Allies

An impressive career for a plane that nearly faced the scrap heap.